For å lese pluss-artikler må du være abonnent

Et abonnement gir tilgang til alt innhold og vi har følgende tilbud

NYHET

“I understand that this is controversial, but the public has a legitimate need to know, and it is important that it is possible to freely discuss alternate hypotheses on how the virus originated” Birger Sørensen starts to explain when Minerva visits him in his office one morning in Oslo.

Despite the explosiveness of his statements and research, Sørensen remains calm and collected.

Sørensen has been a point of controversy ever since former MI6 director Richard Dearlove cited a yet to be published article by Sørensen and his colleagues in an interview with The Daily Telegraph. The article claims that the virus that causes Covid-19 most likely has not emerged naturally.

“It’s a shame that there has already been so much talk about this, because I have yet to publish the article where I put forward my analysis”, Sørensen says in the form of an exasperated sigh.

Together with his colleagues, Angus Dalgleish and Andres Susrud have authored an article that looks into the most plausible explanations regarding the origins of the novel coronavirus. The article builds upon an already published article in the Quarterly Review of Biophysics that describes newly discovered properties in the virus spike protein. The authors are still in dialogue with scientific journals regarding an upcoming publication of the article.

News outlets are thus confronted with a difficult question: Are the findings and arguments Sørensen and his colleagues put forward of a sufficiently high quality to be presented and discussed in the public sphere? Sørensen explains that they in their dialogue with scientific journals are encountering a certain reluctance to publishing the article – without, however, proper scientific objections. Minerva has read a draft of the article, and has after an overall assessment decided that the findings and arguments do deserve public debate, and that this discussion cannot depend entirely on the publication process of scientific journals.

In this interview with Minerva, Sørensen therefore puts forward his hypothesis on why it is highly unlikely that the coronavirus emerged naturally.

On May 18th, WHO decided to conduct an inquiry into the coronavirus epidemic in China. Sørensen believes that it is important that this inquiry looks into new and alternate explanations for how the virus originated, beyond the already well-known suggestion that the virus originated in the Wuhan Seafood Market.

“There are very few who still believe that the epidemic started there, so as of today we have no good answers on how the epidemic started. Then we must also dare to look at more controversial, alternative explanations for the origin,” Sørensen says.

Birger Sørensen and one of his co-authors, Angus Dalgleish, are already known as HIV researchers par excellence.

In 2008, Sørensen’s work came to international attention when he launched a new immunotherapy for HIV. Angus Dalgleish is the professor at St. George’s Medical School in London who became world famous in 1984 after having discovered a novel receptor that the HIV virus uses to enter human cells.

The purpose of the work Sørensen and his colleagues have done on the novel coronavirus, has been to produce a vaccine. And they have taken their experience in trialling HIV vaccines with them to analyse the coronavirus more thoroughly, in order to make a vaccine that can protect against Covid-19 without major side effects.

“The difference between our approach and other vaccine manufacturers is that we have a chemistry background, and we analyse the virus in detail as if we were making a drug,” Sørensen starts to explain.

“Biology is also chemistry, so by considering the virus from a chemistry perspective, we carry out more detailed analysis, zooming in on certain components.”

Sørensen takes us through the basic elements of their approach:

“The first thing you need to establish is which parts of the virus are changing, and which parts are stable. If you want to make a vaccine that lasts, you must stimulate the immune system to react against those parts of the virus that are constant, otherwise the effect will disappear and, in the worst-case scenario, lead to increased illness.

“Once we know this, we can try to make a vaccine. Where we differ is that we are trying to make a vaccine that uses elements that have as little in common with the body’s natural components as possible, so that the immune system is taught to recognise exactly what the vaccine should protect against”, Sørensen elaborates.

Sørensen believes this is an important insight which will prevent the immune system from being falsely stimulated in a way that could lead the vaccine to create too many dangerous side effects in the vaccinated person.

“When we have not succeeded in creating an HIV vaccine, despite the enormous efforts put into that endeavour for the past 30 years, it is because we haven’t understood this,” Sørensen continues.

He believes that there has not been enough interaction between the part of the pharmaceutical industry that makes HIV medicines and the part that runs the vaccine research. As a consequence, the knowledge you need to make a successful vaccine against HIV in the big pharmaceutical companies has not been adequately exploited by the big, international HIV preventing vaccine studies that have been carried out.”

Asked about what significance his approached has had when he has analyzed the coronavirus, Sørensen explains:

“We have examined which components of the virus are especially well suited to attach themselves to cells in humans. And we have done this by comparing the properties of the virus with human genetics. What we found was that this virus was exceptionally well adjusted to infect humans.”

He pauses for a second.

“So well that it was suspicious,” he adds.

It is already known that the novel coronavirus, like the virus that caused the SARS epidemic in Southeast Asia in 2002-2003, could attach itself to the ACE-2 receptors in the lower respiratory tract.

“But what we have discovered is that there are properties in this new virus which enables it to use an additional receptor, and create a binding to human cells in the upper respiratory tract and the intestines which is strong enough to produce an infection,” Sørensen elaborates.

Sørensen says that it is the use of this additional receptor that most likely results in a different illness in Covid-19 patients than the one resulting from SARS.

“This is what enables the virus to transmit to a greater degree between humans, without the virus having attached itself to the ACE-2 receptors in the lower respiratory tract, where it causes deep pneumonia.

“That is also why so many of the Covid-19 patients have mild symptoms at the start of the illness, and are contagious before they develop severe symptoms,” he adds.

It might also explain why some people are ‘super spreaders’ without being ill themselves, Sørensen says.

In the already published article Sørensen and his colleagues Angus Dalgleish and Andres Susrud describe what they claim is curious about the spike protein of the coronavirus, which makes it especially well suited to infect humans. These findings are the foundation for the hypothesis Sørensen and his colleagues develop in the new article, where they claim that the virus is not natural in origin.

“There are several factors that point towards this,” says Sørensen. “Firstly, this part of the virus is very stable; it mutates very little. That points to this virus as a fully developed, almost perfected virus for infecting humans.

“Secondly, this indicates that the structure of the virus cannot have evolved naturally. When we compare the novel coronavirus with the one that caused SARS, we see that there are altogether six inserts in this virus that stand out compared to other known SARS viruses,” he goes on explaining.

Sørensen says that several of these changes in the virus are unique, and that they do not exist in other known SARS coronaviruses.

“Four of these six changes have the property that they are suited to infect humans. This kind of aggregation of a type of property can be done simply in a laboratory, and helps to substantiate such an origin,” Sørensen points out.

Asked about whether this implies that the virus is not natural, Sørensen goes on to explain the laboratory process that leads to the creation of new viruses.

“In a sense it is natural. But the natural processes have most likely been accelerated in a laboratory,” he explains. “It’s also possible for a virus to attain these properties in nature, but it’s not likely. If the mutations had happened in nature, we would have most likely seen that the virus had attracted other properties through mutations, not just properties that help the virus to attach itself to human cells.”

Sørensen vividly explains this argument:

“Imagine that you have cultivated a billion coronaviruses you have gathered from nature, then you take this mass of viruses and inject them into a human cell culture from for example the upper respiratory tract. As a result, a few of these viruses will change in order to better attach themselves to this type of cell in the nose and throat region and therefore to infect humans more easily. You end up with a virus with a spike protein which is perfect for attaching to and penetrating human cells.” Sørensen explains.

Asked about the particular mutations in the virus that lead to this conclusion, Sørensens says:

“What we see is that an area that you could observe in the first SARS coronavirus has been moved, so that the parts of the virus that are particularly well suited to attach to humans, have become part of the spike protein that the virus uses to penetrate human cells. And it is this moving of the area of the virus which makes the virus, together with the injected areas explained above, able to utilise an additional receptor to infect humans.”

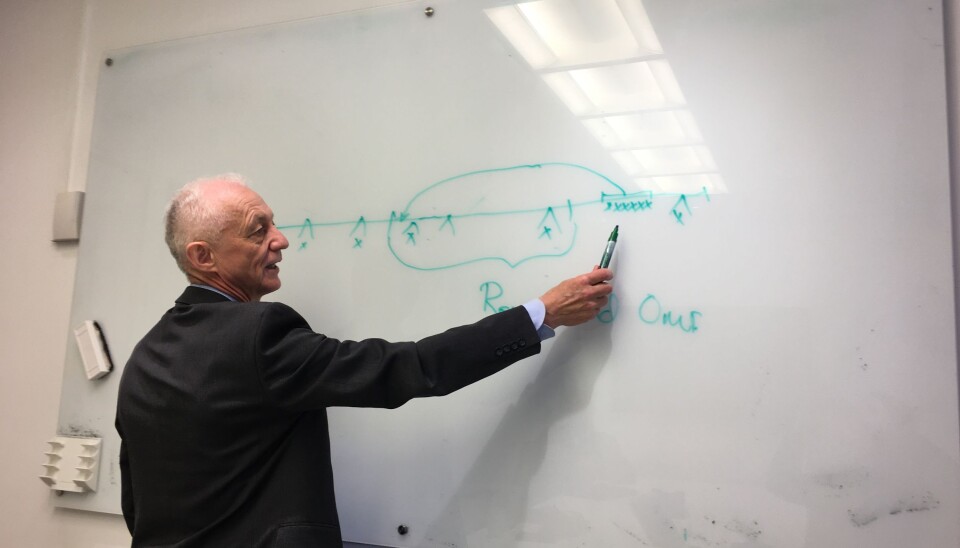

On a board in the meeting room where Sørensen is hosting our meeting, he illustrates what he is trying to explain, and how a component of the virus which previously was situated on another part of the shell of the virus, now has become a part of the spike protein of the virus.

Sørensen is therefore quite confident that the virus has originated in a laboratory.

“I think it’s more than 90 percent certain. It’s at least a far more probable explanation than it having developed this way in nature”, Sørensen responds.

Sørensen also highlights other data than those related to the virus’ properties:

“The properties that we now see in the virus, we have yet to discover anywhere in nature. We know that these properties make the virus very infectious, so if it came from nature, there should also be many animals infected with this, but we have still not been able to trace the virus in nature.

“The only place we are aware of where an equivalent virus to that which causes Covid-19 exists, is in a laboratory. So the simplest and most logical explanation is that it comes from a laboratory. Those who claim otherwise, have the burden of proof,” Sørensen says.

There are indeed earlier known experiments where changes to the corona virus have been engineered. An interesting example of this kind of research is a collaborative effort between Wuhan Institute of Virology and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In a 2015 article, Menachery et al. describe experiments with laboratory created corona viruses – so called gain-of-function-studies. The purpose of this research is partly to be better prepared for new pathogenic variants of the virus. But the researchers also write: «the potential to prepare for and mitigate future outbreaks must be weighed against the risk of creating more dangerous pathogens». This risk must also be evaluated in light of previous known accidents where corona viruses have escaped from laboratories in China.

But several researchers have already pointed out that artificially created viruses would be easy to identify. We therefore ask Sørensen why this has not been identified earlier.

Sørensen believes there are several reasons for this.

“The first is that this is a very uncomfortable finding, and the production of new scientific articles that can be used to prove such findings has all but ground to a halt. Chinese scientists no longer publish articles that can be used to support such a hypothesis”, he says.

“And newer articles that are published about the virus must be thoroughly investigated, especially in relation to the basic material that is being used,” Sørensen expands, and points to a new x-ray article published in Nature by Shang et al., which Sørensen also earlier has criticised for being misleading.

“To do my analysis, I have therefore had to go back to the source material, and look at those articles that were published before the Covid-19 outbreak, where we have chosen to assume that the data that have been used is okay and reflects the actual conditions,” Sørensen says.

Asked about why there has not been more debate on this topic Sørensen has several explanations.

“This quickly becomes a discussion on politics, rather than science, Sørensen responds.

“Nobody wants to put forward the inconvenient truth, many scientists are also concerned about their own funding and position if they were to put forward such a controversial hypothesis. It is nevertheless a fact that many people on the web have engaged in such a debate. But so far, those who participate in such forums are characterized as conspiratorial. It is also the case that a debate about this type of viral research and the technologies used may damage reputation and lead to new restrictions on how to conduct molecular genetic research. With this in mind, it is not difficult to see that it must be difficult to get accepted papers in peer reviewed journals that focus on such research", Sørensen elaborates

Sørensens himself is Chairman of the board at Immunor, a company which is working to develop their own vaccine candidate for Covid-19. Minerva has challenged him to address allegations that this hypothesis is launched publicly to attract funding for his own research.

“Of course, it’s in my interest that my research becomes known, but I am being completely open and have declared all my interests.

“At the same time, I argue that it must be possible for those of us who work for smaller biotechnology companies to present our findings and get them discussed properly. If anyone wishes to contest my findings, they are of course welcome to do so, but I hope they will engage thoroughly with the arguments rather than derail them by discussing my motives,” Sørensen responds.

***

Translation from Norwegian by Kathrine Jebsen Moore